Every year on July 3 we celebrate the enslaved Africans who boldly took their freedom from Gen. Peter von Scholten, the then Danish governor of the Danish West Indies. I think something more needs to be done in celebrating Emancipation Day in the Virgin Islands. What about founding a place where people can visit year-round and learn our emancipation history? A living history that Virgin Islanders can be proud of by telling their story of emancipation.

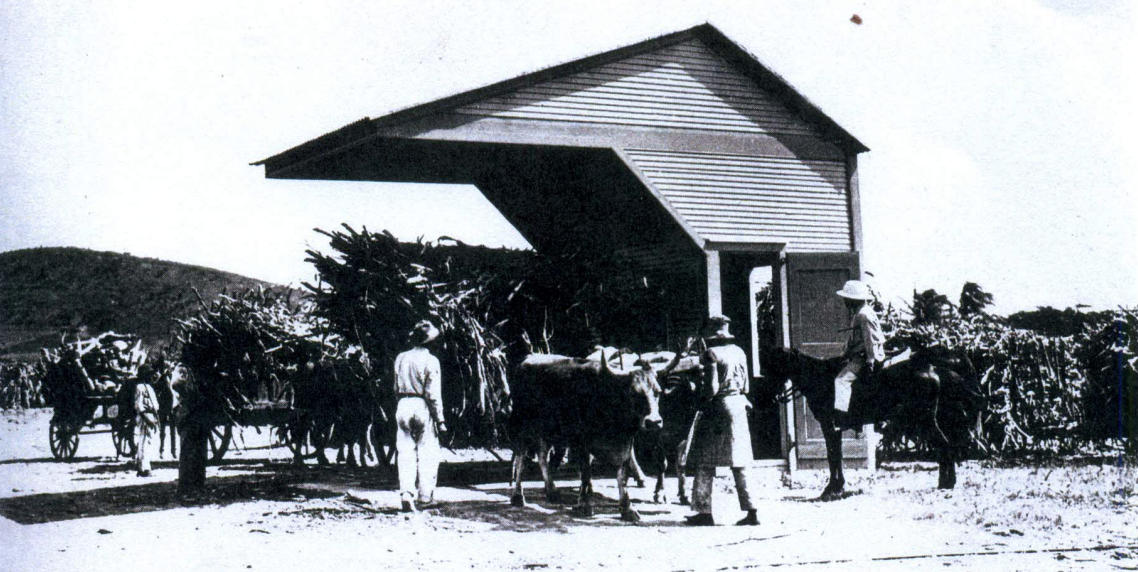

It is just a thought. What about creating a museum at Estate La Grange, the old sugar factory where General Buddhoe and other enslaved people worked at one time? After all, the government of the Virgin Islands owns part of Estate La Grange, which includes the sugar factory once leased by the Brugal Rum Corporation. The colonial history of La Grange extends back from the English in the 1640s. In 1641, the English established a colony on Salt River’s western shore. They also colonized the west end of the island, establishing their principal plantation that is known today as La Grange.

After the English drove off the Dutch, they were ousted by the Spanish expedition, which in turn was uprooted in 1650 by the French. A force of 160 men, sent by the Lieutenant General of the French West Indies, Philippe de Poincy, drove out the Spanish. After the French defeated the Spanish, they set up two large royal plantations, one on each end of the island. Bassin (Christiansted) on the east and La Granderrie on the west, which is known today as Frederiksted.

The French also erected an earthen battery on the La Grange plantation shoreline at present-day Frederiksted. This was a wise decision by the French because they were able to repel the Dutch attempts to destroy La Grange sugar plantation in 1689 and 1690. Nevertheless, after recurrent droughts and epidemics that weakened the French presence on St. Croix, they decided to abandon the island in 1696 for Haiti.

As a result, the island grew back into forests. St. Croix was left to runaway slaves (Maroons) and poor British squatters until 1733 when the Danes purchased the French title to the island. Frederick Moth, the first governor of St. Croix, rediscovered the old French earthwork ruins of what he called “Le Grand.” He reported that, “The walls are visible, some even in a very good condition.” Moth knew the reputation of La Grange as the best plantation on the island under the French and the water resources from the small river known today as La Grange Gut.

With La Grange’s reputation of being the best plantation on the island, Moth reserved the site for the Danish West Indies and Guinea Company. However, the Danes paid more attention to Christiansted development than the West End of the island. Thus, La Grange in the West End became a haven for runaway slaves. The enslaved Africans constructed rafts and canoes made from native trees of the island for flight to Puerto Rico. In 1747 to 1748, the Danes broke up a Maroon camp and established a settlement in Frederiksted with a fort to protect the area and put Estate La Grange back under sugarcane cultivation.

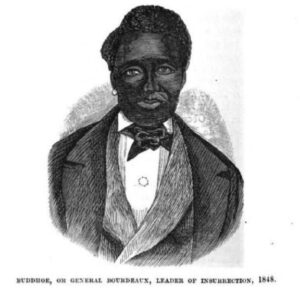

The history of Estate La Grange sugar factory and the operation of the site is interesting. However, I want to focus briefly on how La Grange sugar plantation became part of the emancipation movement and the importance of establishing the site as a museum. John Gottliff, who we know in history as “General Bordeaux”, “Buddhoe,” “Buddo,” or “Moses Gottlieb,” was born on March 19, 1820, as an enslaved person at the Estate La Grange sugar plantation. He appears in the censuses of 1841 and 1846 belonging to the Lutheran Church. Buddhoe also was a member of the big gang. His father’s identity was unable to be ascertained in research documents, but his mother’s name was Maria Rosina, who also was born enslaved on La Grange sugar plantation in 1799.

In 1818, his mother was listed as a field worker. According to the censuses of 1841 and 1846, she was a member of the big gang. Historical documents mentioned that Buddhoe had two sisters. They were Mathilde Petrus, born in 1829, and Leah (aka Sanchy) Petrus, born in 1832. Their father was John Peter Petrus, also an enslaved person at Estate La Grange in 1801. In 1846, Buddhoe’s mother married Anthony George. He was a rat catcher at Estate Little La Grange, which is less than a mile from the Estate La Grange sugar factory.

Anthony George joined his wife, Maria Rosina Buddhoe, in 1850 where the couple lived and worked together on La Grange plantation until 1860 when both moved to Frederiksted. In 1873, George died in Frederiksted. Nevertheless, a year before the “Fireburn” in 1878, Buddhoe’s mother died suddenly from a hemorrhage in 1877. John “Buddhoe” Gottlieb played a major role in the organization plans for emancipation along with Moses Robert, Martin King, and others of the 1848 slave revolt in the Danish West Indies.

These leaders were conscious of the anti-slavery movement in the Caribbean region, especially in the British colonies of the West Indies. They were fully aware of the abolition of slavery in the British West Indies colonies in 1833, as well as in the French colonies in May of 1848. Those enslaved on Estate La Grange and other estates, especially in the west, northwest, northeast, and southwest of St. Croix organized themselves to take their freedom from chattel slavery of the Danish West Indies.

The establishment of a museum at La Grange sugar factory is a place where our history needs to be told to the world. What better way than to create a museum there? One of the best slave museums I ever saw in the Caribbean was in Curacao. Believe me, the history is so overwhelming that it will make the hair on your body stand up.

How many of us knew that Buddhoe had a daughter named Rebecca Bordeaux, and that her mother was Eliza/Elise/Ann Eliza Jackson? Her mother was a free woman of color living in Frederiksted when Rebecca was born on Dec. 16, 1841. This story can be told in the museum where schoolchildren, visitors, and residents alike can learn about Virgin Islands history. Before President Joe Biden vacationed on St. Croix with his family during the Christmas season of last year, he signed a bill that designated St. Croix as a National Heritage Area.

Believe me, the old La Grange sugar factory fits the bill. As we celebrate the 175th anniversary of Emancipation, Gov. Albert Bryan Jr. and the 35th Legislature need to honor our ancestors by passing a bill to establish La Grange sugar factory as an emancipation museum. After all, Frederiksted is “Freedom City.”