Author’s Note: St. Croix, once more, stands at a crossroads. The present situation appears unworkable, the path forward uncertain. It is not, however, the first time St. Croix has stood at such a precipice. This historical six-part series explores three moments in the past century – VI Corp, Harvey Aluminum, and Hess Oil – where frustration with the given situation boiled over into radical change. Breaking with the past, a better future for St. Croix was declared, a new foundation laid. These decreed Crucian futures sometimes aligned with the people and sometimes overrode the people. Today, Limetree comes into view at just such a crossroads, and once more the future of St. Croix is up for grabs.

The First Green New Deal (Part 1 – below) (Part 2)

“Conditions in the islands have been desperate,” V.I. Gov. Paul Martin Pearson wrote his superiors in 1931. As the sugar industry collapsed in the 1920s and the Great Depression ravaged the world economy, the United States Virgin Islands entered a tailspin that sank the islands into generalized despair.

And it was on this Caribbean outpost of the U.S. Empire that President Roosevelt experimented with how to turn the tide of economic collapse. Only bold action could meet the moment, Roosevelt argued, and so in 1934 he replaced the faltering plantation economy with robust public ownership of agriculture that redistributed land to homestead farmers, collectivized a modern sugar factory and farming equipment, and operated entirely “on a non-profit-sharing basis” to channel all earnings into social investments in education, housing, and working people.

Roosevelt’s plan for this Caribbean “pivot” of the New Deal, as the New York Times reported at the time, sparked a consequential debate between “the economy of capitalism and private property and so-called planned economy and public ownership” in addressing the Great Depression. Newspapers on the island were less circumspect: this was a dire matter of whether the United States “desires the island of St. Croix to be or not to be a socialist state,” as the St. Croix Tribune put it.

As Roosevelt and his advisors made clear, the results of this Crucian experiment would inform New Deal policies across the U.S. And soon, St. Croix found itself on the front page, above the fold, of major national papers in New York City and Washington D.C. and debated extensively in Black newspapers across Atlanta, Baltimore, Detroit, and Harlem. For it was on St. Croix that the nation thought it could best read the tea leaves about how far to the left of capitalism the New Deal might go.

The Trouble with Sugar

On St. Croix, much of this rested on reinventing sugar cultivation. Sugar cane can’t nourish without the intermediary of ascending prices, an unfortunate trait that tied the Caribbean to spectacular bonanzas of wealth when distant markets roared but fated many an island to the irony of starvation amidst rich farmland when those same foreign markets retreated. The late Robert Merwin once described to me a boyhood scene at the bustling port of Frederiksted: local merchants anxiously awaiting the daily transmission of sugar prices on the radio. “So much,” he reflected, “depended on those prices.”

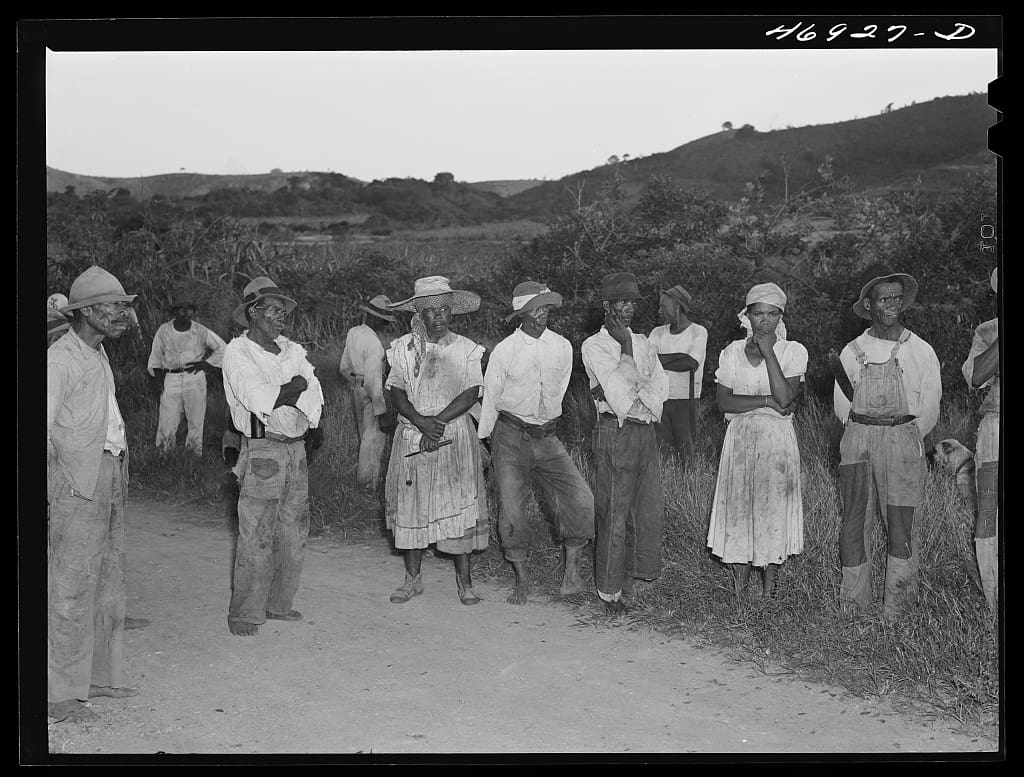

During the famed Dance of the Millions of 1920, sugar prices rose to stratospheric heights only to fall into an epic decline that battered the Caribbean, as some residents quipped, worse than any hurricane they’d known. In 1930, insolvency crashed through West Indian Sugar Company in the Virgin Islands, washing away 13,000 acres of tended land on St. Croix, the last two sugar factories, and stranding thousands of workers and tenant farmers without income. It was at this despairing moment that U.S. President Herbert Hoover visited and issued his infamous description of the Virgin Islands as “an effective poorhouse.” It remains an odd description, missing the more profound paradox: St. Croix was a proud agricultural society finding itself faint from hunger while thousands of acres of fertile farmland fell into disuse.

An aristocratic grip on the land guaranteed the crisis. As the islands sunk into desperate straits, “old owners of the land still clung to their estates” as the New York Times put it. In 1931,70% of the farmland on St. Croix was owned by 14 individuals. Abandoned sugar factories closed off any gainful outlet for sugar cane while estate owners raised rents on tenant farmers well past the point of impossibility. Unemployment touched 50% of the population and one in four was dependent on the Red Cross for food.

An Economy for the People

As Gov. Lawrence William Cramer later reflected, the early 1930s witnessed the vast majority of Black Crucians fast descending into “a landless, dispossessed class with little hope of improving their lot.” Attentive to recent peasant upsurges in Mexico, Egypt, Spain, and above all Russia, perhaps Roosevelt appointees worried rural despair was the going recipe for revolution.

At the January meeting of the Colonial Council on St. Croix in 1934, Roosevelt’s team advanced a bold plan to stave off the worst: charter a new public corporation to seize the plantations, seize the factory, and seize the ports and operate them not for private gain but the public good. Called VI Corp, Gov. Pearson explained the aim of this public corporation: “(a) Make available additional land for homesteading; (b) Make available additional money for building houses on the subsistence plan; (c) Provide aid for new industries organized on the cooperative basis;” with all proceeds invested back into “economic, educational, and social programs” for all residents of St. Croix.

With one million in federal seed money, the VI Corp would purchase large sugar plantations and break them up into five to 10-acre plots for homesteaders. It would also build a modern centralized sugar factory and rum distillery on St. Croix and oversee the exportation of sugar and rum to the mainland. “Public Ownership for Virgin Islands,” ran the front-page headline in the New York Times.

VI Corp would recycle all earnings back into the welfare of the Virgin Islands. As President Roosevelt said at the time, revenue from VI Corp would be invested in “adult education, nursery schools, homesteading, and improved housing” on St. Croix. Initially, this uplift would come through providing low-interest loans to any capable farmer to help them gain title to a plot of prime farmland without restrictions based on race, gender, or current income.

VI Corp would also help these farmers build modern homes and allow them generous use of collectively held farming equipment like tractors and plows. Homesteaders were expected to put half of their land into cane cultivation for export and use the other half for subsistence and local market crops. Substantial investments would also be made in an agricultural station on St. Croix to test out new varieties of crops and to provide educational opportunities for farmers.

Beyond agriculture, the VI Corp promised to bankroll public schools, health care, subsidized childcare, and social security across the Virgin Islands.

“In the US Virgin Islands, the government has gone into business on a grand scale. As farmer, manufacturer, and merchant, Uncle Sam has embarked there on extensive economic planning – some call it experimentation – which, if successful, may help alter not only our national economy but our national philosophy of government,” the New York Times reported.

Lionel Roberts and many labor leaders in the Virgin Islands welcomed Roosevelt’s plan but insisted local unions play a substantive role in VI Corp (this demand resulted in Roberts being appointed the first director of VI Corp a few months later).

Planters and merchants had a very different response. As Governor Pearson said at the time, the affluent “have looked askance at any such project.” But perhaps that’s too polite a summary. As an editorial in the St. Croix Tribune summarized the sentiment: “The proprietary class objects to the wholesale experiment.”

Part two of this six-part series will further discuss the success and impact of VI Corp on the island of St. Croix.

The First Green New Deal (Part 1)

The First Green New Deal (Part 2)

Manufactured Progress: Harvey Aluminum on St. Croix (Part 3)

Manufactured Progress: Harvey Aluminum on St. Croix (Part 4)

David Bond teaches anthropology at Bennington College. He researched the Hovensa refinery in 2010 and 2011 and has written on how the history of the refinery informs the present struggle for justice on St. Croix.