By 2011, Jeffrey Epstein was chafing at the restrictions governing his travel and other reporting requirements as a Tier 1 sex offender registered in the U.S. Virgin Islands, newly unsealed documents in the government’s lawsuit against JPMorgan Chase reveal.

The bank released Epstein’s correspondence with the V.I. Justice Department — where he was required to register and report his travels, among other obligations — late Tuesday after the court denied the V.I. government’s motion to designate the records as confidential.

JPMorgan also released Epstein’s annual filings with the Economic Development Commission, which it claims granted him preferential treatment in the form of more than $300 million in tax incentives over the years, among other benefits.

JPMorgan contends that the documents are key to its affirmative defenses — essentially that the USVI was equally complicit in fostering a climate in which Epstein could commit his alleged human trafficking crimes, through lax enforcement of its sex offender laws, for example — and that the court should treat the government as it would a private civil litigant.

Specifically, JPMorgan asserts “that any damages suffered by USVI should be barred or reduced in accordance with the doctrines of comparative and contributory negligence or fault,” given the territory’s 20-year history “of enabling Epstein’s criminal activity” by awarding his companies EDC benefits, accepting his political and charitable donations, and making sure “that no one asked too many questions about his transport and keeping of young girls on his island.”

The USVI claims that is nonsense, and earlier on Tuesday released its own trove of newly unsealed exhibits alleging that JPMorgan’s top brass continued to court Epstein for his money and ties to some of the world’s wealthiest individuals and failed to alert authorities about suspicious cash transactions even as the bank’s compliance arm warned that he was a growing liability as a felon under investigation for sex crimes.

The V.I. Justice Department’s suit against JPMorgan, filed in December in Manhattan federal court, alleges it aided Epstein’s criminal schemes in violation of the federal Trafficking Victims Protection Act. The bank has denied wrongdoing and has called the suit a “masterclass in deflection.”

Epstein, 66 — a registered sex offender who pleaded guilty to procuring a minor for prostitution in Florida in 2008 — was found dead by apparent suicide in August 2019 while in detention in New York on federal human trafficking charges.

His primary residence was Little St. James, his private island off St. Thomas where for years he trafficked in girls and young women and ran a complex web of shell companies registered in the USVI that enabled his crimes, court documents have alleged.

The wealthy financier, who held some 50 JPMorgan accounts, was valued at more than $577 million at the time of his death, according to court documents.

A High-Flying Multimillionaire

According to JPMorgan’s latest filing, which features 34 exhibits numbering some 500 pages, Epstein sought to bend the territory’s laws to suit his jet-setting lifestyle and at times succeeded, whether through the tenacity of his lawyers who were seemingly on call 24/7, or the incompetence of the DOJ.

“Even as to the regulations USVI did enforce, it did so incompetently. For example, on one occasion, USVI failed to receive Epstein’s e-mail travel notification, and thus failed to notify the jurisdiction where he was traveling of his arrival,” JPMorgan asserts in its updated memorandum of law. “On other occasions, the USVI DOJ was unable to provide any details on Epstein’s travel to other jurisdictions,” it said, citing faxed notices to registries in New York and Florida that were “unsure as to exactly when he will arrive/depart.” Some notices of international travel gave only dates and locations, and that Epstein planned “to travel by private aircraft, N212JE,” it said.

In 2011, as the V.I. Legislature was working to bring its sex offender laws into compliance with federal standards, USVI officials, specifically his office manager, then First Lady Cecile de Jongh, solicited Epstein’s input into the changes he would like to see added to the bill, according to the memorandum. His St. Thomas attorney, Maria Hodge, also exchanged emails and phone calls with the DOJ and then Attorney General Vincent Frazer, arguing the proposed version of the legislation “would create many complications and problems” for her client.

Ultimately, the law passed on June 28, 2012, with Epstein disappointed at the final form of the bill, JPMorgan asserts.

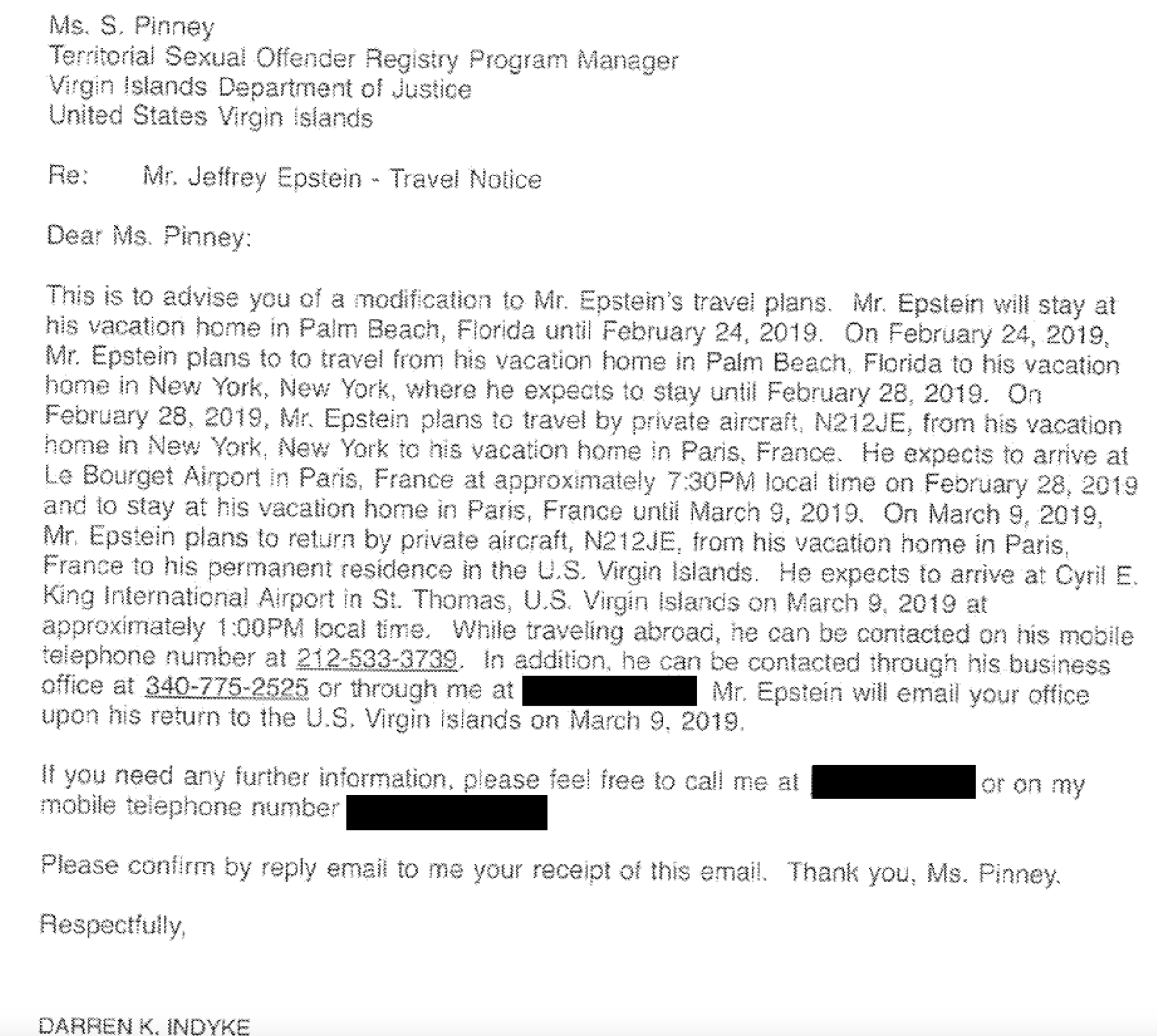

Epstein was still required to inform the DOJ of any travel 21 days in advance, including exact times and dates, where he would be staying, for how long, and his method of travel. He also was required to register as a sex offender every year for 15 years after his 2009 release from jail, provide a list of his vehicles and other means of transportation, his contact numbers, his websites and emails, and submit to home checks.

Hodge and Epstein’s personal attorney, Darren K. Indyke, protested to the Attorney General’s Office that the requirements were more onerous than the U.S. Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act, known as SORNA, and the laws in New Mexico, New York, and Florida, where Epstein owned luxury vacation homes, according to one of the exhibits.

Epstein was “a mature business leader, has paid the debt he owed to society and has returned to business life, now travels with substantial frequency and regularity, and has already demonstrated unerring diligence in keeping the Department of Justice informed of such travel,” said Indyke.

In a July 25, 2012 letter to Hodge, Frazer granted Epstein a waiver of the 21-day travel notice, reducing it to 72 hours, in person, by fax or email with electronic signature, according to the exhibits. Epstein would have to provide information about temporary lodging, including addresses, though foreign jurisdiction lodging could be identified by city and country, including dates of travel and return, and dates he would be staying at an intermediary temporary location. He was to notify the DOJ in person, by email or fax upon his return to St. Thomas.

“I do recognize that these conditions vary from the former conditions. However, in light of the discretion given to the Attorney General by Act No. 7372, we are forced to take a closer look at the waiver conditions,” Frazer wrote.

Still, Hodge pushed back.

In a letter dated July 30, 2012, she wrote, “We appreciate the consideration given to Mr. Epstein’s frequent travel requirements. However, we still have serious concerns regarding what we believe are undue restrictions placed on Mr. Epstein’s travel and the conduct of his business and professional activities.”

Specifically, the 72-hour notice and providing specific addresses of temporary lodging locations when traveling in the U.S. “will have an unduly restrictive effect on his right to travel and conduct his legitimate business and professional activities,” Hodge wrote. She noted that the federal SORNA guidelines allowed for flexibility for those who travel frequently, such as long-haul truckers, or home-improvement contractors or day laborers.

The cases were analogous to situations in the territory, such as pilots, fishermen, boat captains, boat crew, cruise ship workers, merchants and international businessmen, said Hodge. “The burden on both the Department of Justice and the worker of requiring such a worker to give 72-hours prior notice each time he leaves the Territory and to confirm every location and address included in his travel notification would be substantial,” she said.

Instead, SORNA permitted for a “most likely itinerary of ‘normal travel routes’ and ‘general areas’ of work,’” she wrote.

The new legislation permitted Frazer to make exceptions on a case-by-case basis, said Hodge. Epstein, who owned a private plane, often didn’t know his travel dates and destinations with certainty until a few hours prior to his departure, and they frequently changed, she said. By providing notice immediately before leaving, he would reduce the burden on the Justice Department, she argued. In Florida, he just had to let authorities know he had arrived, by email. Her letter also noted Epstein’s “unerring diligence” in providing notice of his travels and other registration obligations, and that he would “endeavor to provide” 24-hours’ notice.

Regarding giving notice of where he was staying, Hodge said that often changed, and that some of his hosts “would be uncomfortable with Mr. Epstein having to provide the addresses of their homes … particularly when the hosts are oftentimes prominent figures whose addresses are not a matter of public knowledge and there is no guarantee that their addresses would not be disclosed in response to FOIA or other Sunshine Law requests.” Otherwise, in the future they may not host him, she said.

On Aug. 14, 2012, Frazer conceded to the requests, according to the emails.

Email Snafu Leads to Changes

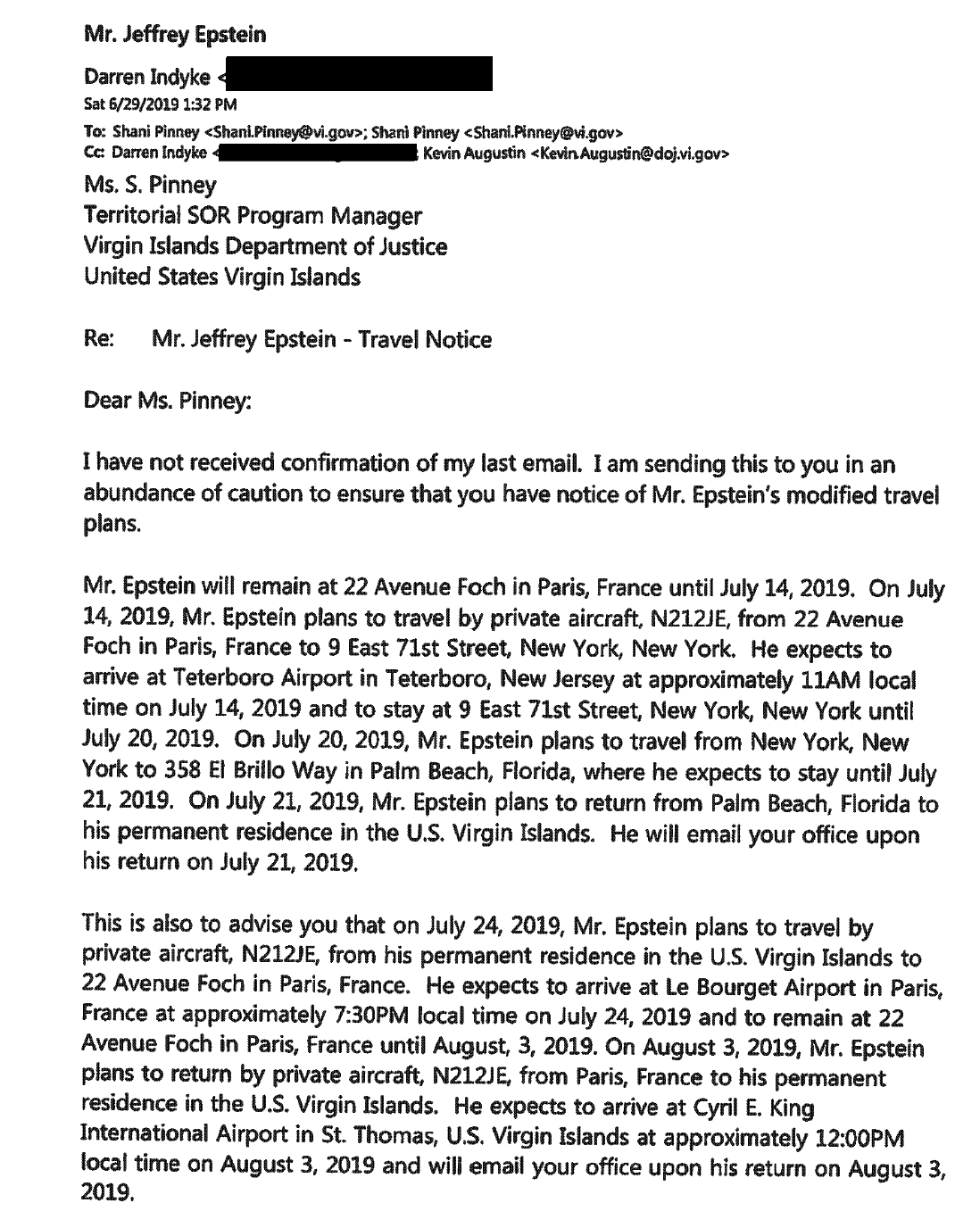

Indyke (most often) or Epstein himself kept the DOJ informed about Epstein’s frequent travel plans, seemingly without much trouble, until a visit to the Dominican Republic went awry in 2019, according to the exhibits.

On April 30, 2019, his then lawyer Erika Kellerhals wrote to then Attorney General Denise George about restrictive new changes that had been made to Epstein’s reporting procedures due to what she said was the DOJ’s failure to notify the Dominican Republic of his travel there for a day trip on Feb. 16, 2019, even though Epstein had notified the department via email.

“Unfortunately, we believe that this incident, caused solely by the USVIDOJ, and not by Mr. Epstein, resulted in additional scrutiny regarding Mr. Epstein’s travel reporting, and that this in turn gave rise to the recent decision to change the travel reporting procedures that have worked perfectly for the past ten (10) years,” Kellerhals wrote.

According to the exhibits, Epstein had been detained by Dominican Republic officials for several hours upon his arrival and was ultimately denied entry into the country.

In response, then Acting Attorney General Carol Thomas Jacobs revoked Epstein’s more lenient notification procedures on March 14, 2019, reverting to the 21-day notice of travel, and requiring that Epstein do so in person.

In an email to Kellerhals on June 2, 2019, George said that while her predecessors might have waived the 21-day requirement, “my role as the Attorney General is to ensure that the laws of the territory are faithfully executed without passion or prejudice,” including the V.I.’s Sexual Offender Registration and Community Protection laws, whose primary purpose was to “protect the safety of the communities from the dangers posed by sexual offenders like Mr. Epstein …”

George said she did not have proof of Epstein’s frequent travel to justify a change to the old rules, nor did the DOJ have any documentation of such proof ever having been submitted to the VIDOJ.

However, it appears from emails in the exhibits that Indyke and Epstein continued to give notice of travel just days before his planned departures, for example, sending an email dated March 30 advising of modifications to his travel on April 2.

The lapses extended beyond Epstein’s travel notifications, according to JPMorgan’s memorandum. On multiple occasions, the DOJ failed to timely make required notifications under SORNA of Epstein’s registration — something Epstein even personally brought up with the authorities in 2017 and 2019, it said. The DOJ also failed to completely maintain the public website of Epstein’s owned vehicles, and site visits to his residence were “cursory at best,” it said.

For example, a report of a site visit to Little St. James on July 16, 2015, noted Epstein was not home and the employees would not let the officer on the island until they contacted Epstein and he gave the OK for an escorted “limited” check. In May 2016, an inspector reported that a person on the island said Epstein had left earlier for last-minute travel and noted, “Verification not completed as Epstein off island.” In July 2018, an agent noted, “Little St. James – denied entry beyond deck * verified @ his office in Red Hook.” Household occupants were listed as Karen and Bryce, adult employees, “age@time unknown.”

The issues all became moot in the summer of 2019, when Epstein planned a trip to his home in Paris, where he was to stay until July 14, when he would travel to Teterboro Airport in New Jersey, to stay at his Manhattan townhouse until July 20, when he would fly to his home in Palm Beach, Florida, before returning to the USVI on July 21.

As was often the case, the plans changed at the last minute, and Epstein ended up flying into Teterboro on July 6, 2019, where he was arrested by FBI agents as he got off his plane on federal charges of sex trafficking minors in Florida and New York. He died in his jail cell on Aug. 19 of an apparent suicide. He had pleaded not guilty and denied the charges against him.

“In sum, in exchange for Epstein’s cash and gifts, USVI made life easy for him. The government mitigated any burdens from his sex offender status. And it made sure that no one asked too many questions about his transport and keeping of young girls on his island,” JPMorgan alleges in its memorandum.

“In short, USVI is a civil TVPA plaintiff like any other, and must answer to the affirmative defenses raised against its pursuit for civil damages,” the bank said.