A bevy of marine scientists, including a Virgin Islands cadre, have identified the cause of a massive die-off of the black Long Spine Sea Urchin in the Caribbean, and now they are looking for ways to stop the killer.

“We don’t have a method for fighting it — yet,” said Marilyn Brandt, a University of the Virgin Islands professor and one of more than 30 scientists listed as co-authors of a study published this week in the journal Science Advances.

Their months-long study concluded that a scuticociliate, a sea-borne, tiny single-celled parasite, had infected the sea urchin species (Diadema antillarum), resulting in the death of masses of the animals that play an essential role in maintaining the health of coral reefs.

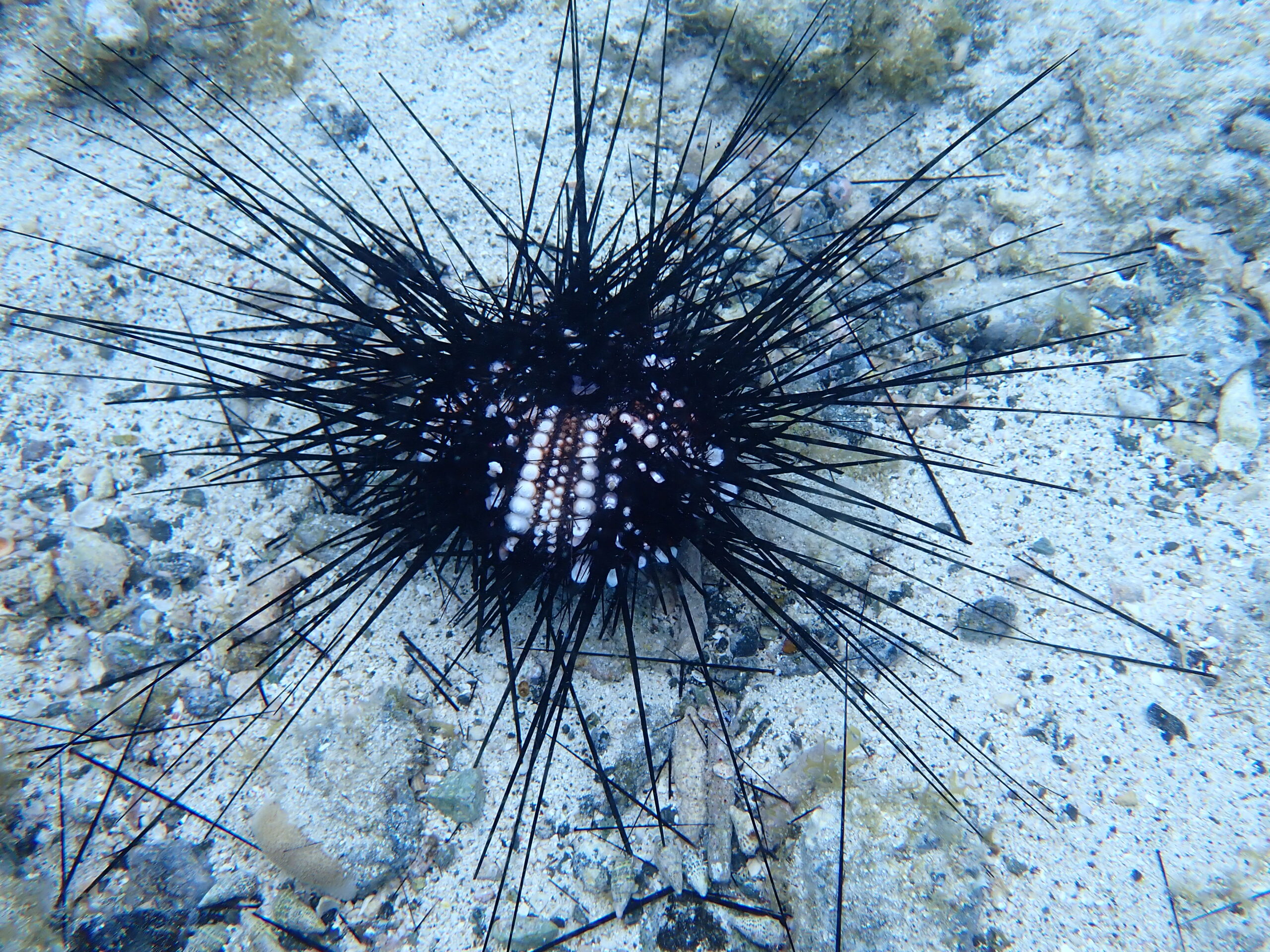

The sea urchin is so slow-moving it can be mistaken for an underwater plant by the uninitiated. It’s easily recognized by its long, hard spines, which can deliver a sharp rebuke to divers or snorkelers that venture too close. But it is essential to reefs, methodically clearing them of algae that might otherwise smother corals.

Once infected by the parasite, a sea urchin is quickly weakened. Its spines begin to droop; it may lean and fall over. It becomes easy prey for its natural predators, which include various species of fish. Eventually, its spines fall off.

Trouble was first spotted in St. Thomas waters by divers who posted reports on social media in early 2022. By February of that year, there were sightings of dying urchins in Flat Cay, Lindbergh Bay, and Black Point off the island’s west end.

“It spread all over” the territory’s waters, Brandt said.

And it spread throughout the Caribbean.

For the study, scientists collected sea urchins from 23 sites around the region, some dying and some healthy. They made comparisons, dissected specimens, and made DNA and RNA analyses.

They had tools unavailable 40 years ago when an even more drastic die-off decimated the region’s sea urchin population.

In 1983 and 1984, the Long Spine sea urchin was “virtually extirpated” in the Caribbean by “an unknown cause,” the study notes.

An estimated 98 percent of the animals were wiped out. Recovery has been exceedingly slow. About 10 years ago, it was estimated that the population was still only 12 percent of what it had been before 1983, according to the study.

The deaths had ecological repercussions.

“The loss of this herbivore (the sea urchin) contributed to change in the competitive relationships between stony corals and benthic algae,” the study says. Along with other factors, it led “to the rapid degradation of many coral reefs across the region.”

Could the same parasite be responsible for both the 1980s die-off and the more recent case?

Maybe. As the study states, the spread of the disease seems consistent in both cases and could be an agent spread by ocean currents over long distances.

But the cause of the earlier event may never be proven because — as far as is known — none of the 1980s specimens was preserved.

For now, the focus is on protecting existing sea urchins.

“Now that we have (identified) this pathogen, we can try more directed treatment,” Brandt said.

She and others are pursuing grants to fund further research.

“Those urchins are so important,” she said. “We’re really hoping these urchins can come back.”

But she had some bad news on that front: while urchin deaths slowed in later 2022, they actually seemed to increase again early in 2023. “It seems to be happening around the same time of year.”

Brandt stopped short of linking the sea urchin die-offs to any specific negative impact on coral reefs, such as the recent outbreak of Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease.

“All of these things are related but it’s very complex,” she said. “It’s hard to draw a straight line” from one event to another.

She does see one highly significant link, however, and that is to human activity.

“We are rapidly changing the environment, and these organisms can’t keep up,” Brandt said.

The study, “A scuticociliate causes mass mortality of Diadema antillarum in the Caribbean Sea,” was a collaborative effort of scientists associated with numerous educational institutions and governments. Ian Hewson of Cornell University is listed as lead author. Besides Brandt, five other authors are UVI affiliates: Kayla A. Budd, Samuel Gittens Jr., Moriah L.B. Sevier, Matthew Souza and Sarah D. Von Hoene. Two others are listed as affiliated with the V.I. Department of Planning and Natural Resources: Erin Bowman and Matthew Warham.