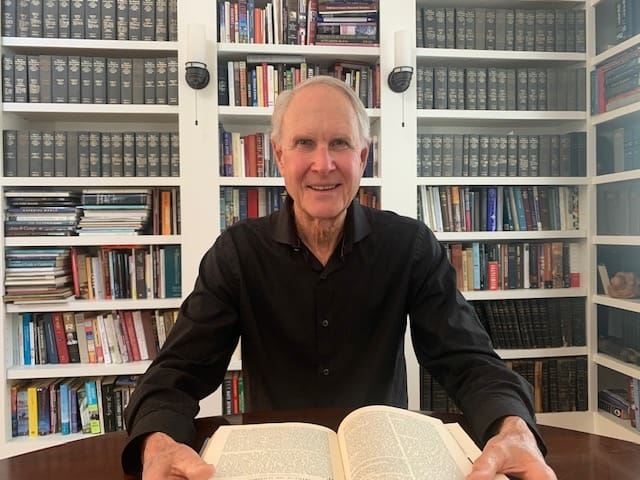

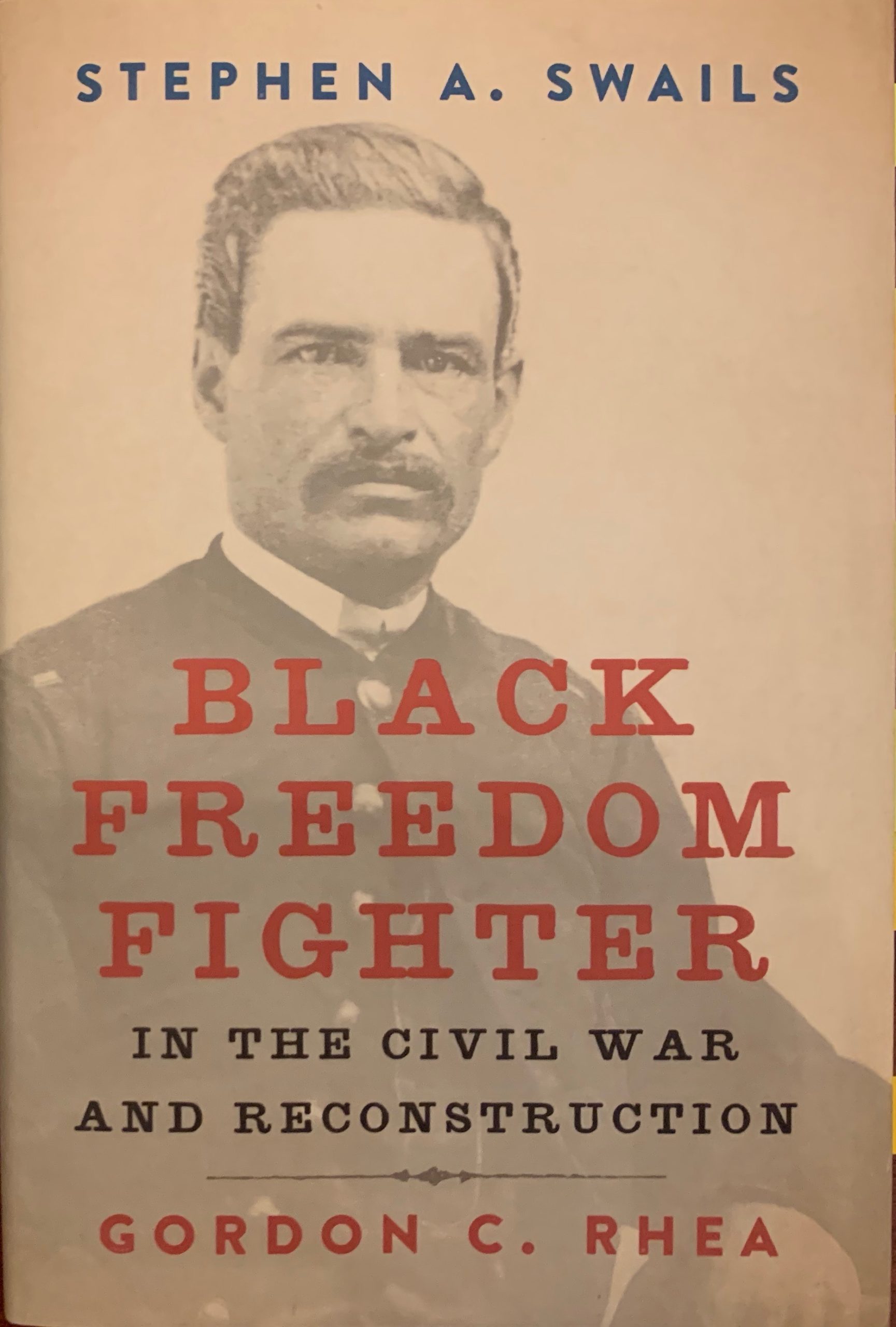

LSU Press released Virgin Islands attorney Gordon Rhea’s latest book, “Stephen A. Swails, Black Freedom Fighter in the Civil War and Reconstruction,” in November. The first printing sold out in two weeks.

Recognized as an authority on the Civil War and its aftermath, Rhea has published seven other books, most of which focus on particular battle strategies in the war. He leans toward biographies these days; this is his second.

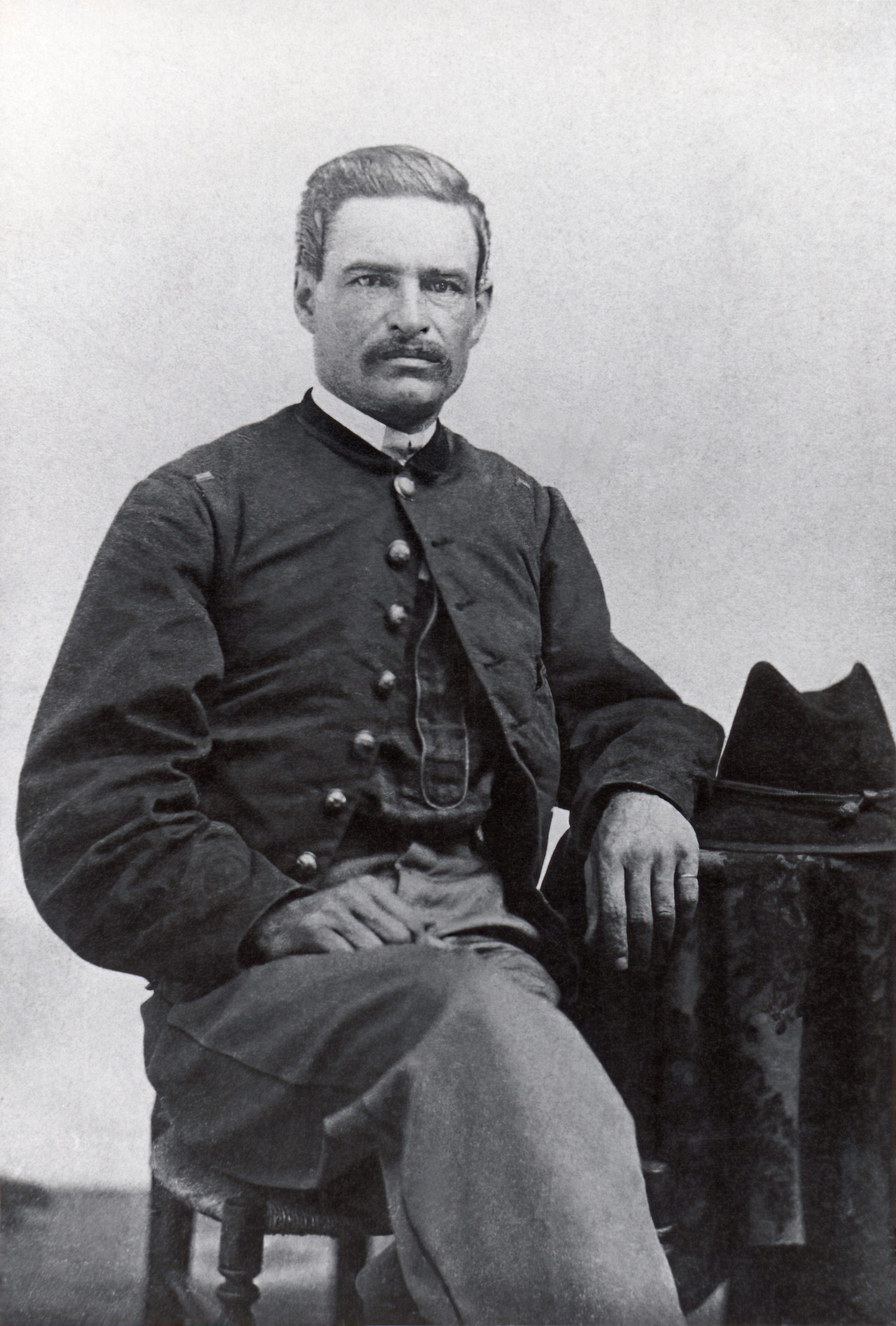

Swails, one of 200,000 Black Union soldiers, fought with the 54th Massachusetts, an all-Black regiment – with white officers – raised by Gov. John Andrew of Massachusetts in 1863. Swails, hailed as a war hero, was the first African American to be commissioned as a line combat officer in the U.S. Military. Staying in South Carolina after the war, he worked with the Freedmen’s Bureau in rural Kingstree and became a leading figure in Reconstruction.

The town elected him mayor, and he went on to become speaker pro tempore of the State Senate during Reconstruction.

Rhea takes us into battles in South Carolina and northern Florida alongside Swails and the 54th. He further recounts the civil rights work of this long-forgotten gentleman, Swails, who was run out of town under the threat of death when Reconstruction ended, and a white supremacist attitude again prevailed.

Rhea opens his book with the tale of an antique trunk left on the roadside for trash pickup in Kingstree in 1978.

Driving their pickup through town one morning, brothers Jimmy and Edward Moore noticed the trunk but thought little of it at the time. Then, on his way to the river later that day, Jimmy spotted the trunk at the dump and pulled in for a look.

Inside, he found Civil War Army records, letters, ledgers from the Freedmen’s Bureau, and other correspondence that had belonged to Swails. Shortly thereafter, the Moore brothers carted the trunk to the county historical society and received a $75 “finder’s fee,” according to Rhea.

The story of Swails came to Rhea via an attorney and historian who was working with the historical society then: William “Billy” Jenkinson. Jenkinson had made copies of the documents before the originals were donated to the University of South Carolina for its historical collection.

“The university never included the papers in the collection and cannot find them now,” Rhea said.

Years later, when Rhea’s wife Catherine was volunteering as a guardian ad litem in Charleston and needed to find a lawyer for a young man in Kingstree, a friend referred her to Jenkinson. He agreed to help with the stipulation that she arrange an appointment for him with her husband. Jenkinson had an angle.

He had read most of Rhea’s Civil War books, including a biography of a white Confederate soldier called “Carrying the Flag,” and had decided Rhea would do an excellent job on Swails. He brought the documents to the meeting, Rhea said.

“Billy and I clicked. I was immediately struck by his idea. I’d been writing in the Civil War and Reconstruction field for 30 years … and I knew right away this was one heck of a find, a gold mine! I jumped on it,” he said.

Rhea said he thinks the Swails saga will appeal to a wide audience as well as to history buffs.

“It’s a fascinating story of human courage and of how much difference one person can make in the advancement of, actually, everybody,” he said.

“Having grown up in the North as a free Black, Swails worked and moved in a Black population but also learned to deal with the white population. He could work in both worlds, and that served him well,” Rhea said.

After the war, Swails studied law, became an attorney, and set up a law firm in Kingstree with a white gentleman who had fought for the Confederacy in battles against Swails and his regiment.

“So this gives you an idea of how Swails operated, how he could bring parties together and could persuade people,” Rhea said.

The Black population understood that Swails advocated for them, and liberal whites respected him, too. He worked with the Freedmen’s Bureau to help emancipated slaves transition to equality, which often required mediation between the races. He set up schools in Kingstree, handled contracts between landowners and freed slaves, orchestrated getting farms for Blacks.

Then Reconstruction ended.

Once the Federal forces pulled out of the South and the federal government “washed its hands of the job of ensuring equality, some of the white population tried to put Blacks back into a situation similar to when they were enslaved,” Rhea said.

“You had a population that had been enslaved and brutalized for hundreds of years, and then, when it finally had a chance at the end of the Civil War, it was a very short chance,” said Rhea, who sees similarities between the post-Reconstruction era and certain present-day tactics: voter intimidation, gerrymandering, and redistricting efforts.

Born in Columbia, Pennsylvania, in 1832 to a mother who was either white or mulatto – census records conflict – and a darker father, who was probably an escaped slave, Swails encountered racial rioting when he was two years old and hid under his bed, terrified. The family fled Columbia and eventually settled in Elmira, New York. Swails, whose light complexion could have allowed him to pass for white, always identified as Black, Rhea said.

While working as a “boatsman” in Cooperstown, New York, in 1863, Swails heard about the 54th Massachusetts regiment. Frederick Douglass and other abolitionists had spread word throughout the Northeast and implored Blacks to sign up. Swails did. The regiment paraded through Boston to a mostly cheering crowd as it left for South Carolina.

Col. Robert Gould Shaw, who commanded the 54th Massachusetts, was impressed with Swails and promoted him to sergeant within two weeks.

When the Federal government reneged on the promised $13 a month pay in favor of $7 for Black regiments, Swails became spokesman for the 54th and demanded equal compensation. The soldiers and the officers both refused pay until the proper amount was secured. That took a year.

Despite his African blood, that Swails could pass for white and be educated and well-spoken finally persuaded the War Department to commission him as a combat officer. Heretofore, the notion of a Black officer potentially commanding whites was more than even most Northerners could stomach.

A historical marker now stands at the site of Swails’ former home in Kingstree, and an obelisk marks his grave in Charleston, thanks to Jenkinson and his colleagues who also arranged for a portrait of Swails to hang in the South Carolina Senate chambers. Although the painting sat in a closet for 13 years, the Senate hung it this month, according to Rhea.

Rhea first visited St. Croix when he trained for the Peace Corps at Beck’s Grove in 1968.

“The Peace Corps leased property there and held an African training program that taught us about daily life and customs in Ethiopia. We learned Amharic through the Foreign Service Institute language program based on total emersion,” he said. “I liked the island a lot. The Hess Oil Refinery had just opened, and all kinds of new people were pouring onto St. Croix.”

Rhea returned to the island in the summer of 1973 and clerked for the Isherwood and Colianni law firm to help pay for law school at Stanford. In 1981, when working as Assistant U.S. Attorney in the District of Columbia, he came back to the territory as Special Assistant U.S. Attorney assigned to the islands. He later set up a law firm on St. Croix with Tom Alkon, 1982-1991.

These days, Rhea splits his time between the Virgin Islands and Charleston. He practices criminal defense and handles civil cases along with giving tours of Civil War sites and lecturing to historical societies across the country.

He’s got ideas on the drawing board: a biography about Governor-General Peter von Scholten, who emancipated slaves in the Danish West Indies in 1848, and another about King Theodore (Tewedros) of Ethiopia. Women in the Civil War fascinate Rhea, too.