Some may say it’s easy to forget or ignore racial strife while in the Caribbean. Many of our towns and streets were named by Europeans, but our elected leaders are usually Black. And the USVI does a pretty good job of keeping its founding Black citizens in the public eye: the Fire Queens, General Buddhoe, and latter-day heroes like the busts of J. Antonio Jarvis, Edith L. Williams, and Rothschild Francis in Post Office Square. The St. John slave insurrection of 1733 and St. Croix labor uprising of 1878 and similar acts of heroics are — or should be — common knowledge to anyone in the territory, be they native-born or transplant.

Early this February, Black History Month, I found a resource that takes a reader back to before many of those people lived. The site, slavevoyages.org, chronicles the trans-Atlantic slave trade year by year, ship by ship. When possible, it lists where the voyages began and ended, the captain of the vessels, and how many captives they carried.

Entering “Danish West Indies” into the site’s search engine pulls up 26 pages of records from 1680 to 1838.

The name of the first V.I.-bound slave ship appears to be lost to history, but a Captain Jones arrived in St. Thomas with an unknown number of human cargo. Three years later, Captain Jean Hamlin navigated the slaver Trompeuse to St. Thomas with 22 souls to be sold.

The data can be sorted in various ways. The Cassada Garden arrived in St. Croix in 1760, carrying just three captives. Disease and violence aboard these ships are well documented, so one can only imagine the horrors these people endured to arrive with so few alive.

In 1762, the Newport, Rhode Island, slave ship Molly left the British-American coast for Cape Coast Castle, Ghana’s infamous slave dungeons. Capt. John Allen embarked with 75 captives. Just 51 got off the ship in St. Croix, 24 people — 32 percent — having died in the Atlantic crossing.

Enslaved people on another ship endured another sort of horror. The Danish-flagged Whydah arrived in 1693 packed with 729 people bound for St. Thomas’ slave auctions. Captain Jean Sage had left Africa with 738 people in chains. Nine of his captives died in that crossing — just 1 percent — but the crowded conditions must have been hellish.

This is not the same slave ship, by the way, as the Whydah Gally, famously captured by the pirate Black Sam Bellamy, for whom Tortola’s Bellamy Cay is said to be named.

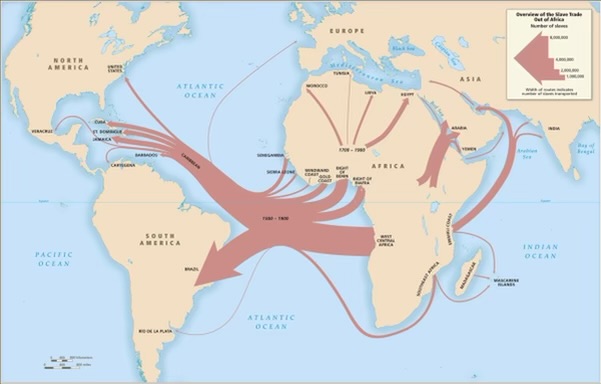

Many of the slave ships started their journey in Europe, particularly Copenhagen, Denmark; Liverpool, U.K; and Nante, France. But a surprising number appear to trade back and forth from the territory to unspecified African ports.

Page after page, it’s a sobering undertaking to imagine the lives of those aboard and what awaited them once they landed. It’s also difficult to put yourself in the mindset of the seamen who transported these people, seeing men and women and children in chains as just part of the job.

The last slave ship to arrive here landed in St. Thomas in 1838, the same year Denmark outlawed the slave trade but 12 years before slavery would officially end in the Danish West Indies. The ship, Con La Boca, left the African port of Sherbro in modern-day Sierra Leone under the command of Captain Jose Ferreira. We don’t know how many people the ship was carrying. We don’t know their names or what they did once they arrived in St. Thomas. We don’t know how many survived to see their freedom from bondage or to what extent their genes live on in us today. We can only reflect on what they went through and how we react to it.

History can be ugly. Really ugly. But there’s beauty there too. It’s entirely possible the poor souls trapped aboard the Con La Boca and the other slave ships are the ancestors of our modern heroes: educators, civil-rights advocates, labor leaders, poets and artists, and legal scholars and merchants of esteem.

Our history lives on in us, informing us, helping us find direction if we bother to seek it out. It’s common for Virgin Islanders to say the ancestors are watching out for us, keeping evil away. Maybe they are. But to me — a white man who grew up in the mountains of Oregon, mind you — it seems it’s up to us to honor them. The ancestors don’t really owe us anything. They’ve served their time here. It’s us who owe them.

So, in the words of J. Antonio Jarvis, “I try to make my sojourn here a useful interlude.”