The following stories highlight the experiences with systemic racism on the American mainland of Black men and women who grew up in predominantly Black communities in the Caribbean.

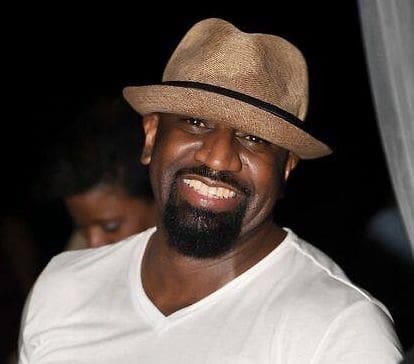

Mario Lanclos grew up in Anna’s Retreat on St. Thomas. He attended Lockhart Elementary School, Addelita Cancryn Junior High School and graduated from Charlotte Amalie High School.

He has lived almost all his adult life in or around the District of Columbia Beltway. He currently lives in Lake Ridge, Virginia.

It was a love relationship that originally lured him to Silver Spring, Maryland, in the fall of 1989. But he soon returned to St. Thomas after Hurricane Hugo, where he got his first experience as a bank teller – which he did full time until returning to Maryland.

It was upon his return to the states that he had his first experience with systemic racism. With his banking experience in tow, he began applying for jobs. He applied, applied and applied some more.

“Even with my experience, no one would call me back.”

He didn’t understand. Finally, after an interview with a Black woman at the Bank of Baltimore, he got it. She told him it was because he was Black and said she would call his references.

Eventually, he was invited for a second interview in front of an entire panel of bankers. He laughs at the memory of that unanticipated “board” meeting.

“Mind you, I wasn’t applying to be the president, just a teller.”

Despite the extraordinary pressure, Lanclos says the interview went well. “Still, no one called me back.”

Some time later, however, he was invited to start training at the Bank of Baltimore, though he already had a year’s experience. All of the other trainees – who were white – had no prior experience.

As demoralizing as his employment stonewalling was, the more than 40 encounters with police over the years is what left him stunningly aware of what it means to be Black in racist America.

The litany of one-sided police run-ins is like a stuck record that, when added up, cost him hours of time and money in bogus traffic tickets, court dates and lost work hours. Not signaling a turn, when he actually had signaled. Looking into a police car as he was driving by it. Passengers in the back not wearing seatbelts. Music too loud. Going over a speed bump too fast. Not wearing a shirt while driving. The suspension on his car too low. Driving with the doors off on a Jeep he had rented with the doors off. Following too close to the car in front of him. Driving too slow.

One time, Lanclos got pulled over in front of the brand-new house he had just purchased in Virginia.

“When the cop got to the where do you live part of the questioning, I said ‘right there,’ and pointed to my new house.”

When the offending officer asked why Lanclos was driving with a Maryland license, “I was like ‘I just moved.’ Nevertheless, the cop wrote him a ticket for driving with an out-of-state license.

On an even more offensive occasion, Lanclos says, “I got pulled over for making a U-turn coming out of the hospital with my two-day-old daughter in the car.”

Lanclos pointed to his newborn baby and said to the cop, “I’ve literally never been on this street before,” and pointed out the absence of a “No U-turn sign.”

“He didn’t care.” Ticket issued.

But the night that still haunts him was far more odious.

After picking up his roommate, Fredo, from Circuit City where he worked a few miles from the bank where Lanclos was employed, Fredo alerted him he was being followed out of the mall parking lot by a police car. Two other Black friends were riding in the back seat having recently arrived from New York City for a visit. Within minutes they were surrounded by eight police cars.

It was in the dead of winter, but the four former islanders were ordered at gunpoint out of the car and told to produce two forms of identification. They remained – as ordered – in the freezing cold for almost two hours, while the police ran countless identification and record checks from the warmth of their squad cars.

“There had been a robbery they said. We fit the description they said.”

All of this despite the fact that everyone in the car had seen the cop following them from Circuit City. And even though Lanclos was wearing a suit and tie, a defensive rather than style conscious habit he had adopted after dozens of traffic stops.

When the cops finally gave up on “finding anything,” on the four – by now nearly frostbitten young men – they were dismissed with a sardonic, “have a good evening.”

Lanclos remembers vividly that no one spoke on the 25-minute ride home.

“We were positive that night that we were going to die.”

Iffat Walker was born and spent her early years in Savan on St. Thomas, where she attended Jane E. Tuitt Elementary School. She left St. Thomas for Atlanta in 1994.

A ghastly family tragedy led to the most shocking and prolonged racist experience of her life.

On Aug. 24, 2006, her brother, Ab-Raheem Muhammad, who had left St. Thomas a year earlier in 2005, was shot and killed by Atlanta police.

“Ab-Raheem was asleep in a vacant apartment.”

She speculates he and a woman friend probably had sex and he fell asleep. The woman, who lived upstairs from the apartment where Ab-Raheem was killed, had gone back to her apartment.

The whole thing, Walker says, was controversial at the time. “The stories kept changing.”

What she has come to believe is some workers in the building saw her brother asleep in the unoccupied apartment and called the police.

“They [police] kicked in the door and when Ab-Raheem jumped up, they shot him in the face.”

The only things in his possession at the time were a bag of potato chips, some Ensure and a candy bar. But those details – including that her brother was shot in the face – were hindsight.

Walker was not to have a clue what happened to her brother for a full week. Worse, she didn’t know for sure that the victim was her brother for 12 or more hours.

“I got a call at work from my best friend’s sister,” the woman who lived in the building where Ab-Raheem was killed. “She said, ‘you need to come here quick.’ I think something has happened to Ab-Raheem.” She thought that because she had not been able to reach Ab-Raheem on the phone.

Walker says she doesn’t even recall leaving work. When she arrived at the apartment complex the medical examiner, police and news reporters were already on the scene.

“I walked up to a reporter, who I later became good friends, with, and asked him what happened.”

The reporter, Tom Jones, said he was told a homeless vagrant had attacked a police officer and was shot.

Walker says she was relived. “That didn’t describe Ab-Raheem.”

Meanwhile, she and her mother, who also resided in Atlanta, kept trying to call him. But no answer.

“We began to worry.”

They drove to the medical examiner’s office, which was closed by the time they arrived. They rang the bell. Finally, someone came to the door.

“When we told them we were trying to find out if the dead man was Ab-Raheem, the person who answered to door asked me to describe him.”

Among other descriptors, Walker said her brother had tattoos. One of them was a dragon. The person asked, “Was it a picture of a dragon, or the word dragon?”

It was then, Walker remembers, that “I knew he was gone.”

The officials told her they would call her.

“We waited and waited.” No one called. Around 2 or 3 a.m. Walker, her mother and an aunt who also lived in Atlanta, went back to the police precinct. They rang the bell. And rang it. Finally, after an hour-and-a-half wait, someone came to the door and took them into a room used to interview people.

“Can we see him,” they asked. “At this point, we were still trusting the police.” In fact, Walker says she was engaged to a police officer at the time.

“Just tell us we can go to the medical examiner’s office and see him,” they pleaded.

But that was not yet to be.

All of that night and the next days were hazy. “Maybe we’re dreaming right now,” she wished and wondered.

Walker still does not remember the order in which the next events took place on the day after Ab-Raheem was killed.

“Co-workers came to the house to take me to the police department. I couldn’t drive.”

When they arrived at the precinct, Walker was escorted to the third floor to what she calls an “interrogation room.” That is where she first met Lt. John Germano.

“He cursed us out.” She had come to the police department for the police report. “I had no idea how that worked.” She was crying. “I didn’t understand why he treated us that way.”

He told us to come back in a week for the report.

The same day, and again Walker doesn’t recall the order of events, she went to the medical examiner’s office. She and her family members wanted to see the body. They also wanted the police to release Ab-Raheem’s remains to the funeral home.

Instead, “They brought the police in,” who started interrogating Walker and her family.

“We are Muslim.” Sharia law dictates that people be bathed and then buried as soon as possible.

But still, she was not allowed, nor was anyone in the family, to see her brother.

An agonizing week passed as family members continued to make their way to Atlanta.

On the appointed day, one week after Ab-Raheem was shot and killed, Walker made her way back to the police station with her mother and other family members to get the police report.

She requested to see Lt. Germano. She was put in an interrogation room with her mother.

“He came in and told me to stop asking questions.” She remembers well, “I was so angry.” She decided to leave.

At that point, Germano grabbed Walker and pushed her against the wall and handcuffed her – all in front of her grieving mother.

“He whispered in my ear, ‘I told you not to bring your ass back here.’”

“I was crying. It was my job to dress the body,” which she still had not seen.

Meanwhile, a female officer asked Germano what he was doing to Walker.

As Germano continued to taunt her, Walker recalls the female officer kept saying, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry.”

Finally, and Walker holds no memory of how much time had passed, Germano “cussed at me and pushed me out of the door into the rain.”

Her memory of that day remains elusive relative to certain things. “I don’t remember how I got to the funeral home,” to which her brother’s body had finally been released.

However, Walker vividly recalls, “When I got there, I was told the schedule had changed and I couldn’t see him. They said they needed more time to fix his face,” adding they did not want to be responsible for more trauma.

A cousin volunteered to view the body. It was not until the relative returned to the waiting family, speechless, that Walker’s family knew what had happened. It had been a full week since Ab-Raheem was killed after being awakened by police officers kicking in a door. It had been a full week since her unarmed brother had been shot in the face by those officers.

What happened to her brother served to awaken Walker to the grimly repetitive and tacitly accepted nature of police violence against Black people in Atlanta and across the country she had immigrated to.

She became and remains to this day a tireless activist and organizer in both Atlanta and the U.S. Virgin Islands. She has had warrants issued for her arrest stateside and her life threatened because of it. At one point she says, “The new Black Panther Party sat outside my apartment for eight months, protecting me.”

Editor’s note: Lt. John Germano committed suicide in 2019.

Related stories:

Racism is Defined by Experience: Prologue

Racism is Defined by Experience: Chapter One